Alive in a Deeper Sense: Dennis Hopper and the Act of Creativity

April 28, 2021

By Stephen Lee Naish

There is a scene in Alison Maclean’s 1999 film Jesus’s Son in which F.H, the film’s lead character played by Billy Crudup is wet shaving Bill, played by Dennis Hopper. Bill is a resident at the same hospital F.H is currently residing in. Whilst in the act of shaving, they have a brief and loose conversation about Bill’s life circumstances. Bill tells F.H that he has been shot twice by his two ex-wives and F.H retorts with some surprise ‘you’re still alive? ’To which the no-nonsense Bill replies “Are you kidding? Obviously, I am.” F.H. clarifies that he really means that Bill’s life is a kind of miracle, and that staring death in the face twice means that he could consider himself ‘alive in a deeper sense.’

This short scene that’s tucked away in a small late-1990s indie drama, one of the hundreds in Dennis Hopper’s filmography, is telling of what Hopper felt was important in art and life, and that the two things were actually one and the same. Art and life mingle in the same room. Art and creativity in general gives life a deeper sense of purpose to one’s existence and vice-versa. The scene also plays out in the context of Hopper’s own existence and the triumph and perceived failure of his early career as a New Hollywood film director. Hopper had had immense early success with his 1969 directorial debut Easy Rider and, on a creative flush, jetted out to Peru to film his 1971 follow-up The Last Movie. While The Last Movie has now been revisited and reassessed as a brilliant art film, the notion at the time was that it was simply too difficult for normie audiences to comprehend. The critical reaction to the film saw Hopper ostracized from an already changing Hollywood environment and what could be claimed as a great directorial comeback with the 1980 film Out of the Blue was at the time dealt the ‘too dark, too difficult’ blow by audiences and critics alike who felt uncomfortable with a film that dealt with the destruction of the nuclear family at the hands of an abused teenage daughter obsessed with punk rock and Elvis Presley. Upon his triumphant acting comeback in 1986 with three stunning turns in Blue Velvet, River’s Edge, and Hoosiers, Hopper was back in the game, reinvigorated, and revived. Shot down twice, but still alive.

This sense of being ‘alive in a deeper sense’ applies a number of times throughout Hopper’s acting and directorial career, and also his work as an artist, photographer, and art collector. The iconoclast filmmaking days of Easy Rider and The Last Movie certainly apply, but so do the later directorial films such as Colors, Backtrack, and The Hot Spot. One just needs to look a little deeper.

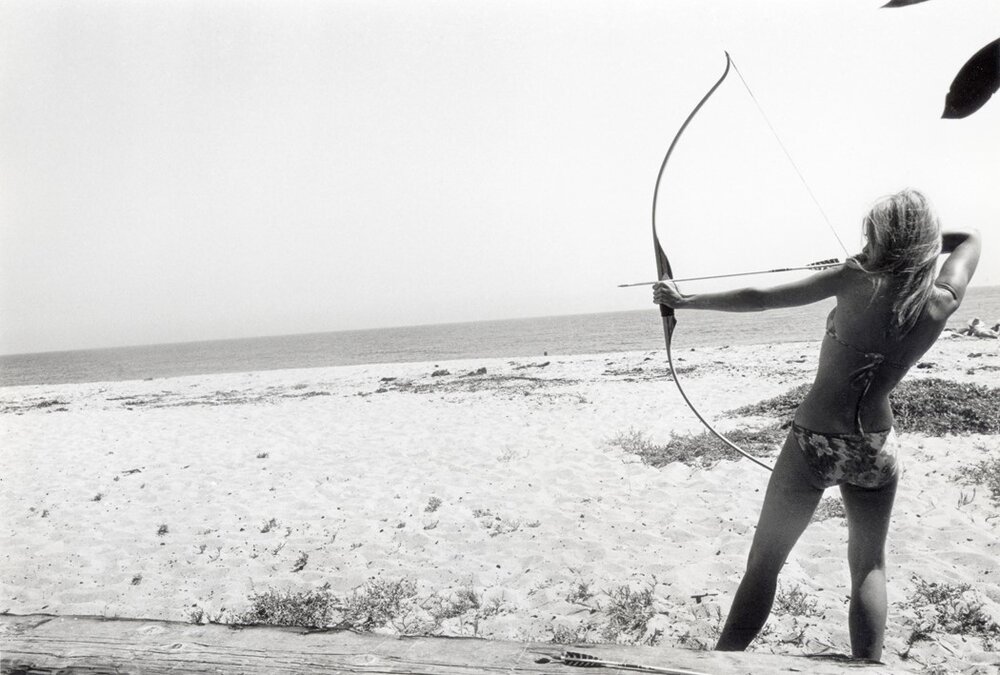

In my book Create or Die: Essays on the Artistry of Dennis Hopper, I attempted to engage with Hopper’s creative life through some of his most well-known movies such as Easy Rider, Apocalypse Now, Blue Velvet, even Speed. But I also explored some of his lesser-known films such as Acts of Love, White Star, and The Blackout to find the nuances of his performances and the why and how of his on-screen style of ‘method’ acting. I also pulled focus on his artistic works in photography, painting, sculpture, and other forms, searching back over decades of work. His photographic work of the 1960s captured the social upheaval in beautiful black and white. His brash and colorful painting of the early 1980s offers a glimpse into the well-documented complexities of his life at that point in time. One chapter looked at the political nature of his work and life, and how once perceived as a hippie radical he switched to being a Republican and supporter of Reagan and Bush, before siding with Obama in the run-up to the 2008 election. Though one could argue his support for more conservative politics was never unconditional. He remained critical. One chapter took a deep dive into the music he used to soundtrack his films and the musical cultures that surrounded him and those that he engaged with such as Bob Dylan, Neil Young, and later the animated experimental band Gorillaz. There were also explorations of his work in print and televised advertisement from his stint with the NFL to Ford’s Cougar.

In the early days of the book, I wanted to uncover all of Hopper’s acting work, however strange, or obscure, but one thing becomes very clear when you spend time deep in the trenches of Dennis Hopper’s varied works: he took it all very very seriously. He saw creativity in everything he was offered, everything he took part in, no matter it seems the circumstances of his life at those points in time.

One might not believe that directing a commercial for Tod’s Pashmy bags held much creative intrigue for someone like Hopper, but when he did indeed direct such an advert in the late 2000s, he threw himself into the project with gusto. Another actor might have turned their nose up at appearing in what might be considered straight to DVD fodder such as Tycus, L.A.P.D: To Protect and Serve, or Out of Season, but Hopper saw these projects by predominantly young untested directors as an opportunity to keep learning and crafting his ability as an actor, but also to help guide this new crop of filmmakers and actors. After all, he’d been in their position once. A familiar face and name such as Hopper’s on the poster or VHS cover would give the film a boost even if his appearance in the said film was brief. The outcome of the movies mentioned above, or the many others one has to sit through (I’m looking at you Space Truckers) in order to comprehend Dennis Hopper’s work ethic may sometimes miss the mark, but there is never any doubt in the viewer’s mind that when Hopper appears the movie just might get a bit more interesting, or that the commitment he shows to the role is never in question.

Hopper’s work in film, either as director or actor, is perhaps his most recognised form. Yet it is worth acknowledging that all the elements of Hopper’s creative life contribute to that film work. For example, his early use of photography was used to understand framing and composition in preparation for his future directorial debut. When you look at the spontaneity of these photos taken in the 1960s they directly link to the way he used his film camera to weave in and around the action in films such as Easy Rider, The Last Movie, and Colors. He also used a lot of stationary shots in his third film Out of the Blue, setting up the camera at interesting angles and letting the action play out in long naturalistic takes. Each scene plays out like a still photograph that has come to life.

One aspect of Dennis Hopper that always intrigues me is the sheer level of discovery that awaits those willing to engage and invest in his work. I started out intrigued by Easy Rider and the surrounding counter culture of that film and continued on thrilled (and unnerved) by his performances in Blue Velvet, and River’s Edge. This led me down the path of discovery into the films he had made in America but also outside. Films such as the Australian 1976 bushranger adventure Mad Dog Morgan, the 1977 Patricia Highsmith adaptation The American Friend, set in West Germany and directed by German director Wim Wenders, and the other strange German excursion of 1983’s White Star directed Roland Klick. The oddest of these foreign adventures is Bloodbath (also known as The Sky is Falling, also known as Las Flores Del Vicio) a strange Spanish surrealist film from the hand of director Silvio Narizzano. When unable to act in American films for whatever reason, Hopper simply upped sticks and went abroad creating an extremely interesting ‘lost’ period of films from 1972 to 1984.

Investigating his film work further led me to come across his work in art and photography, which led me deeper into the cultural impact of his life and times and thanks to YouTube and other online streaming platforms a never ending assortment of interviews, scenes, performances and moments from Hopper’s existence are there for the taking.

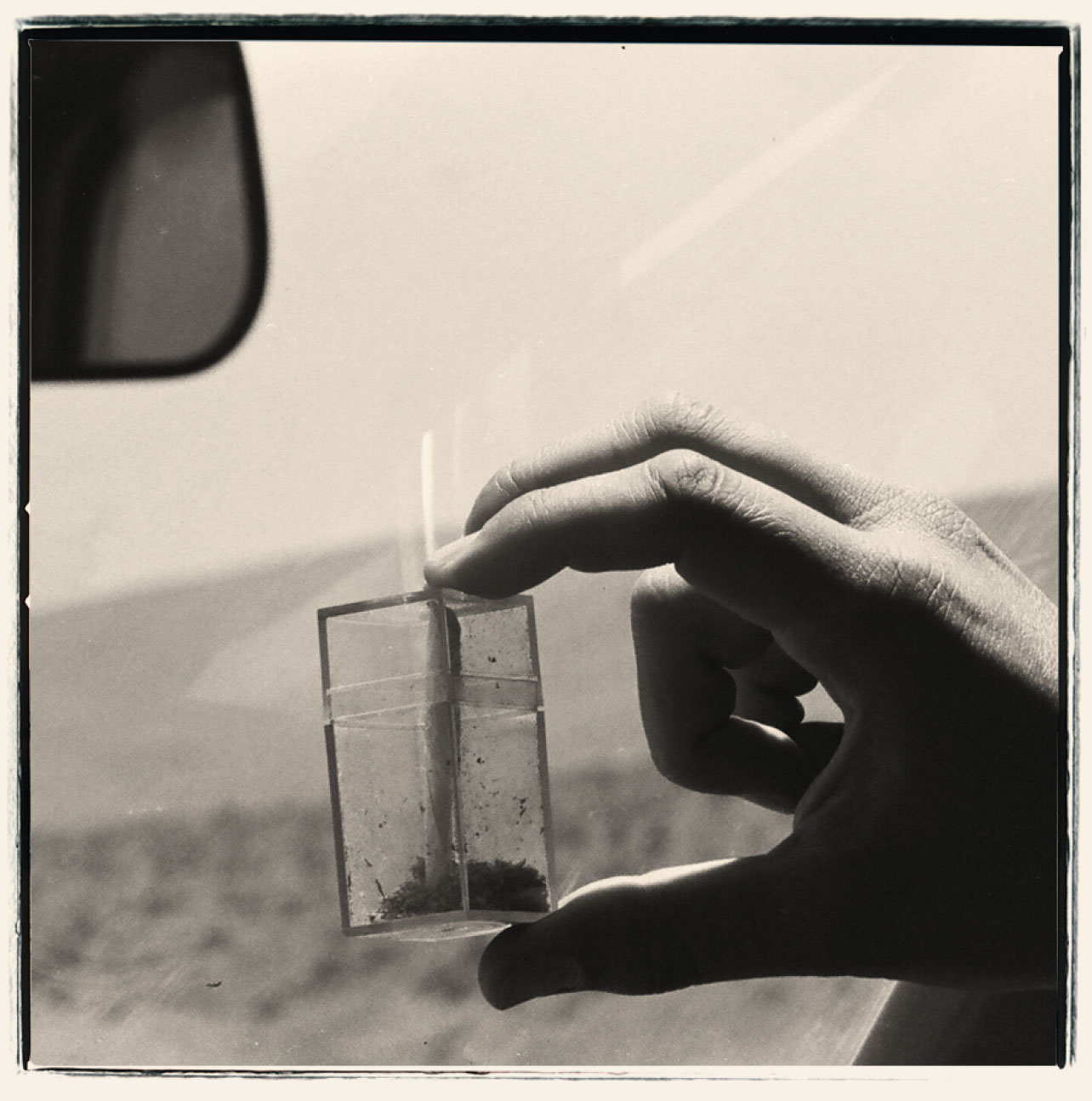

And the discovery is far from over and his impact is still being felt today. Photographs from Hopper’s archives are still being uncovered and released in exquisite monographs, most recently Dennis Hopper: Colors, The Polaroids and Dennis Hopper: In Dreams: Scenes from the Archive. Exhibitions of his art and photography have been displayed worldwide. His directorial films The Last Movie and Out of the Blue have recently been given extensive restorations in sound and visual quality and re-released in cinemas, screened at film festivals, and released on DVD/Blu-Ray. Recently discovered footage of an extensive conversation between Hopper and legendary film director Orson Welles has been issued as a two-hour feature length documentary titled Hopper/Welles that uncovers aspects of the creative nature of film and life from both perspectives. And of course there is now a Hopper branded cannabis called Hopper Reserve that beautifully taps into the spirit of independence and artistic freedom that Hopper bestowed on us way back in 1969 when he, Peter Fonda, and Jack Nicholson lit up a joint around the campfire in Easy Rider and committed to screen one of the funniest and most naturalistic scenes in contemporary cinema.

What more awaits us? Plenty, I’m sure. Here’s hoping that all the artistic worlds inhabited by Dennis Hopper keep revealing their marvelous, funny, inspirational, and creative moments and continue to make us feel alive in that “deeper sense” of the word.

–

Stephen Lee Naish is the author of several books on film, popular culture, music, and politics, including Create or Die: Essays of the Artistry of Dennis Hopper, which was published by Amsterdam University Press. His forthcoming book, Screen Captures: Film in the Age of Emergency is coming in September 2021 with New Star Books. He lives in Ontario, Canada.